The author of Opráski sčeskí historje on how his irreverent comic strip caught fire in a tiny and “dated” corner of the internet

By Jan Velinger

September 19, 2018

Opráski's Zmikund chums around with Charles IV. Photo: René Volfík

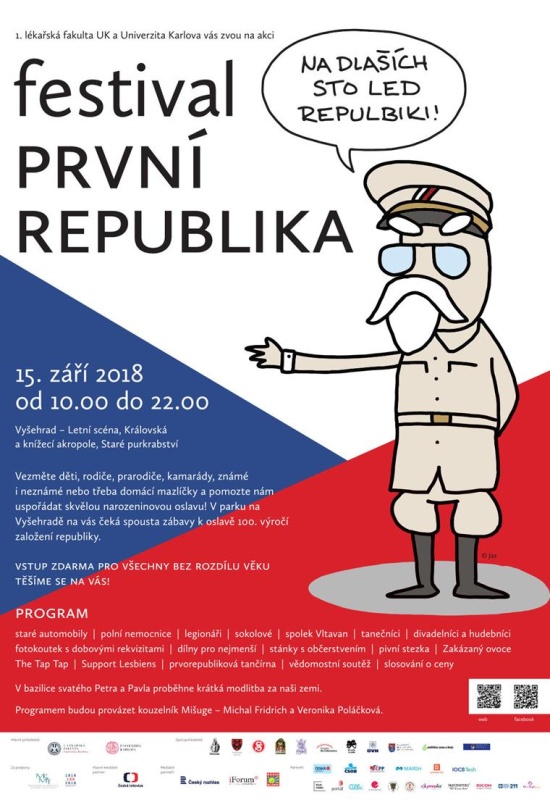

If you are one of the two thousand or so people who attended the První republika festival organised by Charles University (and the First Faculty of Medicine) last weekend, you probably caught sight of a poster of T.G. Masaryk, as drawn by Jaz. He is the anonymous author of Opráski sčeskí historje – an irreverent comic strip that has achieved cult status through an unusual take on Czech history and the Czech language.

My first question to the author, who sometimes appears in public in a paper mask, was whether he has anything special planned for October 28.

“The answer is yes: I always dedicate time and energy to come up with something special when there is an important anniversary and this one is one of the most important. So readers will definitely see not just one strip but maybe a couple on the occasion, if time permits. But the upcoming 100th anniversary of the founding of Czechoslovakia will definitely see a special strip.

“For me it is bigger than the recent 50th anniversary of [the Soviet-led invasion] of 1968, because this is something which can actually be celebrated. This is a positive anniversary.”

The secret author of the cult comic strip gets the last laugh. Photo: René Volfík

Opráski covers the history of the Czech lands and Moravia from the first Stone Age settlements to the arrival of the Slavs and later Christianity, the founding of the kingdom of Bohemia, all the way to modern times. The first comic dates back to 2012. Where did it first appear?

“It began on the internet and by that I mean an obscure corner of it, a discussion board called okoun.cz. Discussion boards of course belong to the late ‘90s and early 2000s, so really stone age technology. But this is a very special place for me where special people, in all aspects of the word, gather. The first Opráski originated there, for a very specific and small group of people.”

What was the first strip?

“I did three or four the first day but the first is the famous Zmikund and [15th century religious reformer] Jan Hus burning at the stake and the second was Forefather Čech (Czech) coming to the mountain Říp.”

And it caught on.

“I was surprised how quickly it caught on. I didn’t expect anything like that, that such an obscure thing could be of interest to more than six or seven people. But then it spread over the internet and the social networks and I was really amazed that there were so many people who were interested. I didn’t expect it - but you never do. You can never predict the full results of your actions.”

In interviews, you often refer tongue-in-cheek to an institution that you call ústaf (a phonetic spelling of the Czech word ústav, meaning institute). This institute is behind the comic but you have made clear that most of the production comes down to you alone. Is that the case?

“Well it is certainly the case that what I call the historickí ústaf or historical institute is both understaffed and underfunded. So yes, most of the time things are just up to me: most of the time I am there alone so have to draw and write everything.”

When I was getting more into the comics, I was surprised to learn that Opráski came under fire for the way you work with the Czech language as well as the drawing style. Some critics charged the style is inartistic and you were also accused of bastardising the Czech language. The Czech language has its specifics and is taught very rigorously at schools and some evidently don’t like what you have done with it. What do you say to your critics?

“First of all, what I say to critics is what Zmikund would say: deal with it! By the way, the charge that the style is inartistic is spot on. The artistic style is exactly as it should be because the comic is based on internet memes. These, by definition, should be drawn poorly or seemingly poorly. I take this as a compliment.

“As for the language: the Czech language is very, very flexible and allows you to do a lot of crazy things with the structure and meanings. It’s true that it is taken very seriously by a great many people; but if you have material that is so rich with opportunities, why not explore it?

“Some people might be offended, but others discover something interesting in it.

“As for the wave of criticism, it did not last long: in 2012 it was something that really shocked some people but I think that a lot of people just weren’t familiar with some of the things commonly found on the internet. Once it became more public, in printed form, I think it lessened. And by the way, when it was first published on okoun, it was only ever intended as very light humour. But for mainstream people it was shocking.”

On the flipside, you get good marks from historians for your treatment of the history itself. It may be satirical, but you are faithful to the history.

“Yes and in a sense you’ve got to be. If you didn’t build the strip around a real basis it probably wouldn’t be funny. So you have to stick to the essence of the event and the story. The fundament has to be true – and then you can play with it.”

Either you were there or you missed a heck of a party. Poster for First Republic Festival.

You are pushing at the boundaries of past interpretations or accepted interpretations of given events.

“This is what any historiography itself does: each event has unlimited potential and unlimited points of view. If you look at an event such as a battle, you have winner and a loser and the event will be viewed differently by the participants: the division is very sharp and it is actual history and maybe actual science, actually?! Why couldn’t my look at history be different?”

As the author you have for years been the subject of speculation because you go under the artistic name of Jaz but keep your true identity secret. You are anonymous and there has been plenty of speculation whether you are an historian and someone at either the Czech Academy of Sciences or at one of the universities such as Charles University. I want to ask you about your anonymity in a moment, but first, the name Jaz (pronounced Yaz). It sounds like it is short for jazyk – which in Czech literally means tongue… and of course also language. So coincidence – or not?

“Um… I will probably not comment on this (laughs). Definitely it is an interesting angle.”

You mentioned that language is something that is very flexible: it’s evolving and changing. For most people throughout history, the spoken word was more important than the written one: most people couldn’t read or write. Another aspect of the comic, seems to be that you are writing a little how people speak and also the way they can mess up the language: on one side of a hill they say it this way, by the time it gets to the other side they have a different way of saying it. I wanted to ask if you were touching upon that angle as well.

“Definitely. The phonetics of a language and how you pronounce versus how the words are written is interesting and important. Another reason why Opráski are written as they are is because of the influence of language on the internet. This is all combined in the comics and over the years I developed some rules and a style which are not ad hoc.

“I believe that readers can spot them and understand was well. One of the criticisms about the language was that it was a bad influence on children. But that was a basic misunderstanding: just because something is drawn in a comic strip does not mean that children are the intended audience. In Opráski, they certainly aren’t.”

Which should be clear within the first few frames, based on some of the expressions used. At the same time, my son, was drawn to the illustrations and glanced at it. Even though there are many which are not age-appropriate for him, I was kind of secretly proud that he got the joke.

“Yeah and I don’t think it’s anything wrong. When I was 10 I read How I Won the War and found it hilarious although I didn’t get a lot of jokes especially regarding sex and other things which I only got when I re-read the book when I was 15 or 16. But I don’t think it left any lasting damage to my soul. I developed mostly properly.”

Alright. Anonymity: is it just cover in your case, to protect your privacy?

“Opráski doesn’t have to be mixed in with the rest of my life and what I am doing. That is why I chose to remain anonymous. It is also funny and it brings something special to the comic. It is more funny this way.”

It’s more fun for you…

“And for others, I think.”

People love an Easter egg hunt.

“Exactly.”

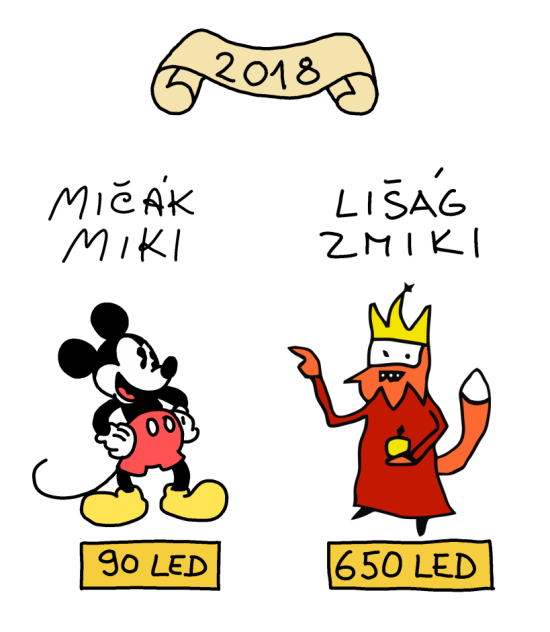

Mickey, meet the old kid on the block. With permission from the author.

If I want to follow Opráski for the latest content, where do I go?

“The main way is still on my facebook page and I have a twitter account where I duplicate the content. But facebook is the easiest way.”

The essence of the comic is that it is just four frames: have you considered a longer format?

“Four panels is the classic form of internet meme comics and I find it most suitable. It gives you enough space to say something but still make your point. Ninety-five percent or more of the comics are four panels with a few exceptions, such as a single panel. But four frames is the most suitable and that will not change.”

To sum up, which period of history did you enjoy when you were studying, high school or otherwise?

“I always liked medieval history and modern history and obviously there is a pattern of that in the comic. And when I say medieval and modern history I mean from the Czech perspective. Consequently, I have done hundreds of comics from those periods with Czech figures and only a handful, for example, of Habsburgs from the 17th century.”